Page Content

Adrian LaChance performs at the opening of the annual DEHR conference.

Meaningful reconciliation requires a departure from the superficiality that marks much of society’s understanding of indigenous society and a move toward an appreciation of the depth and complexity of indigenous history, knowledge and beliefs.

That was the message shared by Dr. Alex Wilson during her keynote address at the Alberta Teachers’ Association’s 2017 DEHR conference, at Barnett House on April 27. Originally from the Opaskwayak Cree Nation in Manitoba, Wilson is a community activist, an antiracist educator and the academic director of the Aboriginal Education Research Centre at the University of Saskatchewan.

|

“We have an opportunity now in this era of reconciliation to not only acknowledge but validate and return to an indigenous understanding of knowledge and knowledge transmission.”

– Dr. Alex Wilson, keynote speaker |

“We have an opportunity now in this era of reconciliation to not only acknowledge but validate and return to an indigenous understanding of knowledge and knowledge transmission,” Wilson said.

Wilson compared knowledge transmission and culture to an iceberg, with seven-eighths of the mass hidden below the surface. Most people know only the “above the water” aspects of indigenous culture such as music, clothing and food, she said.

“It’s the stuff below the water that we’re most interested in because, for the longest period of time, we’ve been fixated on the above water when we talk about culture, when we talk about education and knowledge.”

The colonization process that has taken place since Europeans arrived in North America, including the residential school era, has resulted in the top of the iceberg becoming scraped away from the bottom, she said, to the point that non-aboriginals and even aboriginal people lack a deep understanding of indigenous culture and knowledge.

“For many, that top of the iceberg now becomes their whole understanding of what indigenous culture is,” Wilson said. “This isn’t just non-native people doing it. We start doing it ourselves because that’s what we have access to.”

Wilson challenged the merits of multiculturalism, which she said touches only on superficial aspects of culture.

“Multiculturalism feels good … because you can dance, you can celebrate cultures … but the reality is nothing changes,” she said, citing examples such as the high suicide rates and dropout rates experienced by aboriginal people.

She advocates for an anti-oppressive, land-based approach that promotes the understanding of indigenous peoples’ world views, philosophies, knowledge systems and teaching practices, which have been developed over thousands of years.

“For all of those years we had an intact education system,” she said. “We didn’t just survive, we thrived.”

|

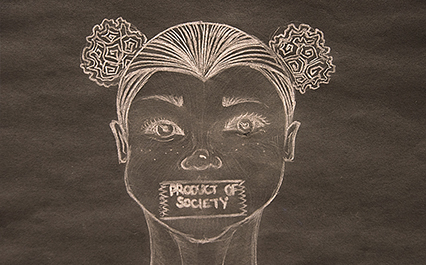

Student art on display

at the conference |

She also challenged the roughly 80 in attendance to think very seriously about reconciliation, comparing the concept to advising an abused woman to stay with her abuser.

“It has to do deeply with power relationships that have upheld some groups and oppressed others, so when we say reconciliation, what do we actually mean?” Wilson said.

“This is something that takes some time to unpack and think about … without forcing people into reconciliation because maybe some people don’t want it,” she said.

“The truth is the relationship has not been an equal one, historically.” ❚

|

Dr. Sheelah McLean

conducts a workshop

at the DEHR conference. |