Page Content

MicroSociety brings the real world into school

At Aspen Heights Elementary School, in Red Deer, the highest office to which a student can aspire is that of prime minister.

Annika Erickson, an employee of the Penguin Avenue food vendor, greets customers with a smile along with the hotdogs she’s prepared.

But those who aren’t politically inclined can try for police chief, banker, cook or a range of other occupations … there is literally a job for everyone. There are also other true-to-life realities, like bank accounts and income tax. All this is thanks to the school’s MicroSociety program, which aims to prepare students for the real world by giving them experience in real-world activities.

“We wanted something that would motivate our students. They seemed kind of apathetic about education,” explains Milton Williams, one of the teachers who co-founded the initiative, and its first co-ordinator.

Aspen Heights is the only school in Canada to provide a program sanctioned by Philadelphia-based MicroSociety International. The school’s involvement came about three years ago after a group of six Aspen Heights teachers visited a pair of schools in San Diego, Calif., to witness MicroSociety in action. They couldn’t believe what they saw students doing, largely on their own.

“We came back all so excited because it was what we needed to breathe some new life into our school,” Williams says.

The routine

What began as a six-week trial now permeates every aspect of life at Aspen Heights. At the beginning of the school year students vie for election in roles such as prime minister and deputy prime minister. Every class elects a member of parliament. There’s a health minister and a minister of business.

The next step is the hiring of managers for the 17 or so ventures that are part of MicroSociety. These include a smoothie business, bookstore, newspaper, radio station, wellness centre and a charitable organization called Helping Hearts.

The managers then recruit staff at a school-wide job fair. Every student who doesn’t already have a position applies for three jobs and gets three interviews; teachers help them with their resumes.

Each enterprise is run as closely as possible to the real thing. The bankers, for example, wear white shirts and ties (a dress code they decided themselves) while keeping track of everyone’s accounts. The Royal Aspen Micro Police (RAMP) enforce school rules and hand out tickets.

After roles have been assigned, the students attend Microuniversity – 10 one-hour sessions tailored to their specific roles: management, laws, taxes, customer service, etc. In many cases, experts from the community provide guest presentations on their occupations.

The activity culminates in three market days, during which the various ventures sell their goods or services for stingers, the school’s own currency.

On the case

One of the main premises behind MicroSociety is that, as much as possible, students make decisions for themselves, Williams says.

As an example, he shares a story of a student who was heading up the police force buying uniforms from a local T-shirt supplier. Aware of his budget, the student consulted his officers to decide what they wanted and handled the arrangements himself.

“The lady at the business, she was so impressed that a Grade 5 student could handle all that and do all that without a teacher stepping in to handle it,” Williams says.

He says the MicroSociety program is a natural at delivering on the three E’s (engaged thinkers, ethical citizens and entrepreneurial spirit) and 10 competencies that Alberta Education has outlined as its stated goal of curriculum redesign.

And it’s not only the academically inclined who thrive in the MicroSociety environment, he says, but also those on the margins of academic success.

“We’re developing a lot of resiliency in these kids, critical thinking. Solving problems is really big,” he says. “They do it every day.”

He shares another anecdote to illustrate the power of MicroSociety.

There was a boy in the school that he describes as “hard to reach,” who was suspected of stealing about 400 stingers from a till.

The police chief investigated. The accused said he’d earned the money so the chief checked with the bank and found the numbers didn’t add up. The accused then said he’d gotten the money from his friend. The chief interviewed the friend and concluded that this explanation was false. It all culminated in a court appearance for the hard-to-reach kid.

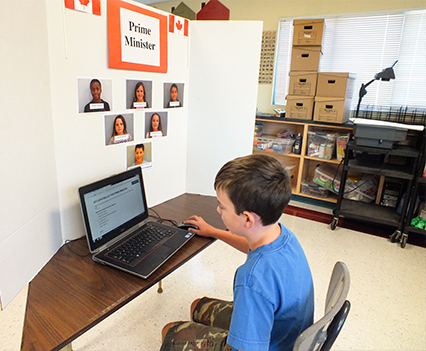

Grade 3 student Nathan Butler puts in his electronic vote for prime minister during MicroSociety elections.

“We couldn’t get any emotion out of this kid but when he went to court before his peers there was real emotion coming out,” Williams says. “He admitted it and he was sorry for it.”

Staying power

To Williams, the program is different from the “bandwagon jumping programs” that tend to come and go in some schools and districts.

“This is the first one I’ve ever seen in my 25 years that I think is long lasting, that really, really meets a lot of needs of the students,” he says.

The change experienced at Aspen Heights has been nothing short of transformative, agrees teacher Allan Baile, the school's MicroSociety co-ordinator for this year.

When the program first started, the students were tentative, he says. They aren’t anymore.

“The biggest thing that Micro does is give our students confidence,” Baile says. “When visitors come to us, that’s the first thing they say. ‘Your students are so confident and so knowledgeable.’” ❚