Page Content

|

ATA 101 is a feature series aimed at informing members, both new and experienced, about various aspects of the Alberta Teachers’ Association.

This instalment provides a brief glimpse of the history of unions in North America and beyond. Watch for additional instalments in upcoming issues of the ATA News.

|

Rebellions by working people denied means to protest their grievances against employers have ancient roots. Slave rebellions in the Roman Empire and strikes by day labourers in medieval cities are examples. But it took the Industrial Revolution of the late 1700s and gathering large groups of workers in factories to create the ongoing collective organizations of workers that we now call unions. The grim conditions of work that Charles Dickens portrayed convinced many workers that they could achieve more by combining their forces than as individuals.

Rebellions by working people denied means to protest their grievances against employers have ancient roots. Slave rebellions in the Roman Empire and strikes by day labourers in medieval cities are examples. But it took the Industrial Revolution of the late 1700s and gathering large groups of workers in factories to create the ongoing collective organizations of workers that we now call unions. The grim conditions of work that Charles Dickens portrayed convinced many workers that they could achieve more by combining their forces than as individuals.

The term “trade union” emerged because most workers who initially combined their forces in Europe and then European colonies were trade-based. These were skilled workers who demonstrated solidarity within their trade via unions. Unions sought to bargain with employers on behalf of their members to improve wages and working conditions.

Until the 1870s, such efforts were considered illegal. In Britain, for example, combination laws from 1799 until the Trade Union Act of 1871 defended the right of employers to deal with each worker as an individual, labelling organizations that wanted collective negotiation by workers as “combinations in restraint of trade.”

Between 1914 and 1920, teacher organizations formed in all of Canada’s provinces. Pictured here is the first board of the Canadian Teachers’ Federation, which formed in 1920.

Though collective bargaining and strikes were illegal, a general strike in Scotland in 1820 involved 60,000 workers. The state crushed their revolt. Other illegal strikes followed, and on the continent, the unions played important roles in the attempted overthrow of monarchies in 1848. With bans unworkable, governments eventually passed legislation that gave trade unions a legal status but constrained their operations so that the union’s institutional funds could be seized if an employer’s interests were harmed by workers’ actions, including strikes.

While unions had varied ability to force employers to bargain, most also became member insurance organizations. They used union dues to aid workers and their families without income because of illness, work accidents or temporary unemployment. Unions also lobbied for all workers, or at least male workers, to be enfranchised since most countries restricted the vote to entrepreneurs and homeowners.

Repression and politics

By the late 19th century, the relative success of trades in improving their status encouraged many less-skilled, easily replaceable industrial workers such as coalminers and railway labourers to form industrial unions that organized all workers in a workplace or industry into one union. Governments and employers responded with repression. That encouraged unionists to sponsor socialist parties that called for the replacement of private ownership of enterprises with public ownership. In turn, the threat that an organized working class posed for owners of capital drew concessions from otherwise conservative governments in favour of blue-collar workers.

That began in Germany in the 1880s, where Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck had initially responded to worker activism by banning the Socialist Party and placing unions under government surveillance. When he recognized that such measures increased the restiveness of workers, Bismarck introduced sickness insurance, accident insurance, and old-age and disability insurance to persuade workers that the system could respond to their needs. Only blue-collar workers were covered, though over time, pressure from other workers made these programs universal.

In North America, where industrialism came later than in Europe, both governments and employers proved more resistant to worker-friendly changes. The Canadian Trade Unions Act of 1872 legalized unions but not collective bargaining. Employers faced no legal requirement to bargain, and contracts signed with unions were unenforceable.

Until the Great Depression, North American unions were heavily weighted to the trades. High unemployment before the First World War prevented most Canadian workers from unionizing. A major issue for workers who did unionize was to reduce the workday, which was often 10 hours, six days a week to nine hours, five days a week. The concept of a “weekend” was unknown in the 19th century before union struggles gradually made it a reality for their members.

During the war, labour shortages removed workers’ fear of dismissal. Production workers and civic employees alike opposed high wartime profits that came at the expense of wages that failed to match inflation. Not only did workers threaten strikes to get concessions from employers, but they successfully persuaded unionized workers in other workplaces to also threaten to strike in a show of solidarity that might cause their employers to pressure the recalcitrant employer to accept union demands.

In September 1918, Calgary freight handlers, facing threatened federal back-to-work legislation, persuaded half the city’s unionized workers to join them in a general strike if the government failed to quickly come to an agreement. They did. One month later, the Edmonton local of the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE) was only able to reach a settlement with the railways after the unions belonging to the Edmonton Trades and Labour Council threatened a solidarity strike if the railway companies did not settle with the CBRE.

As the war ended, and unemployment returned, Canada’s vastly expanded union movement confronted employers determined to reverse workers’ wartime gains. The continuing erosion of workers’ wages by inflation and the lack of social policies to protect unemployed or ill workers created militancy across a wide spectrum of the working class.

In 1919, metalworking and construction unions in Winnipeg, stymied by obstreperous employers, decided to strike and asked other unionized workers to join them. On May 15, when the strike started, many were surprised when 35,000 Winnipeg workers walked off the job, two thirds of whom were not even unionized. They stayed off the job for six weeks until the federal government used force to end the strike. The Winnipeg General Strike had echoes in other cities, including Calgary and Edmonton, where many unionized workers went on strike for about a month. Everywhere the demand was for employers to accept the right of workers to unionize, to bargain collectively and to strike when agreements could not be reached.

Teachers join the movement

Among groups that began to unionize during the First World War were white collar workers, including teachers. Teachers had many complaints. School boards often dictated what they could wear and how they ran their personal lives. Pensions were unknown. Teacher pay was poor and female teachers were paid far less than male teachers. The Saskatchewan Union of Teachers, formed in 1914, led the way in the formation of provincewide associations. The BC Teachers’ Federation, whose first convention was in 1917, was second, followed the same year by the Alberta Teachers’ Alliance. Several associations were formed in Ontario, beginning in 1918. When the Canadian Teachers’ Federation was founded in 1920, every province had at least one provincial organization of teachers. The first teachers’ strike in Canada occurred in Victoria in 1919. It was a successful two-day strike to win pay hikes.

Union membership across North America dipped precipitously after the First World War in the face of an employer assault and high unemployment. Pro-union legislation promoted by President Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s countered employer resistance, allowing industrial unions to establish in manufacturing plants.

More conservative governments in Canada deterred similar successes here. Only Nova Scotia and Alberta, in 1937 and 1938 respectively, passed legislation before the Second World War to legalize and enforce collective bargaining contracts. During the war, with unemployment again vanquished, the Canadian union membership doubled and the labour movement successfully pressured first the federal government and then all provincial governments to legislate collective bargaining procedures.

Until the late 1950s, the Canadian labour movement consisted mostly of male blue-collar workers. But white-collar workers had begun to unionize as well, including supermarket employees and municipal workers. In the 1960s they were joined by provincial and federal employees, including professionals in female-dominated sectors such as nursing, teaching and social work.

Until then they had been low-paid workers with little control within their workplaces. They were members of associations that had earlier downplayed collective bargaining, regarding strikes as uncouth. Now they demanded to be treated as highly trained professionals who merited pay and decision-making participation befitting their credentials and challenging work. They raised such issues as understaffing, overwork and opportunities for professional development. Like blue-collar workers before them, white-collar professionals demanded decent benefits, paid vacations and ample old-age pensions. They were willing to strike to achieve their demands.

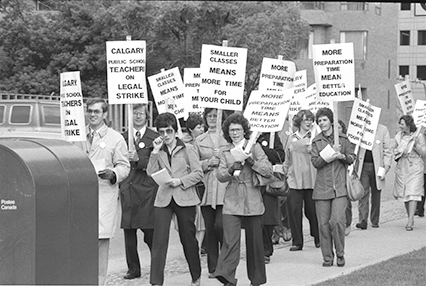

The first teacher’s strike in Canada occurred in Victoria in 1919. Here teachers from the Calgary Public local walk the picket line during a 1980 strike that resulted in 41 school days lost.

The labour movement had always been involved in politics, lobbying for union-friendly legislation and for social programs of benefit to working people. Union pressure was a key factor in winning universal medicare in Canada. Lobbying for healthy social programs became even more important as public sector workers became the majority of trade unionists.

In 2020, 31.3 per cent of Canadian non-farm workers were covered by a collective agreement. That represented a 6.4 per cent decline from a peak in 1981. Declining employment in the manufacturing sector, austerity campaigns in the public sectors, and the prevalence of precarious/casual employment in the burgeoning, largely non-unionized service sectors, all present challenges to a Canadian labour movement that is nonetheless almost three times as strong as its American counterpart thanks to somewhat more labour-friendly legislation. Studies showed that the “union effect” for workers includes better occupational health and safety provisions, better wages and benefits, better opportunities to launch successful grievances against employers and an additional year of life expectancy. ❚

Alvin Finkel is author, co-author or co-editor of 13 history books, including Working People in Alberta: A History. He is president of the Alberta Labour History Institute and professor emeritus of history at Athabasca University.