Page Content

Introduction

Sustainable educational leadership and improvement preserves and develops deep learning for all that spreads and lasts, in ways that do no harm to and indeed create positive benefit for others around us, now and in the future.

—Andy Hargreaves and Dean Fink

This article shares an abridged version of a large research study on leading and sustaining school improvement conducted by Rosemary Foster, Lisa Wright and Philip McRae. The study explores the relationship between leadership practices and sustainability of successful Alberta Initiative for School Improvement (AISI) projects over an eight-year period. The full report is available on the Internet at www.education.alberta.ca/aisi.

The findings of this study are important at a time when AISI initiatives are weathering the harsh realities of a 50 per cent reduction in funding announced by the Government of Alberta in 2011; a direction that may threaten the legacy and sustainability of their site-based action research projects focused on student engagement, learning and performance. It is hoped that the results of this comprehensive study will indeed be timely for those interested in sustaining leadership practices and innovative school improvement activities.

Background

The AISI projects reviewed in this article reflected a complex blend of formal and informal leadership approaches at school and district levels. In these projects, educational leadership was often characterized as a process whereby influence is exerted by one person (or group) over other people (or groups) in an effort to structure and facilitate relationships and practices that have the potential to enhance student learning (Yukl 2002). Along with exploring how educational leadership was defined, developed and practised over eight years of AISI activity, this research examined how promising educational innovations are implemented and sustained within Alberta classrooms, schools and jurisdictions. In addition, the practices and structures that support or serve as barriers to the sustainability of educational innovations were documented and identified.

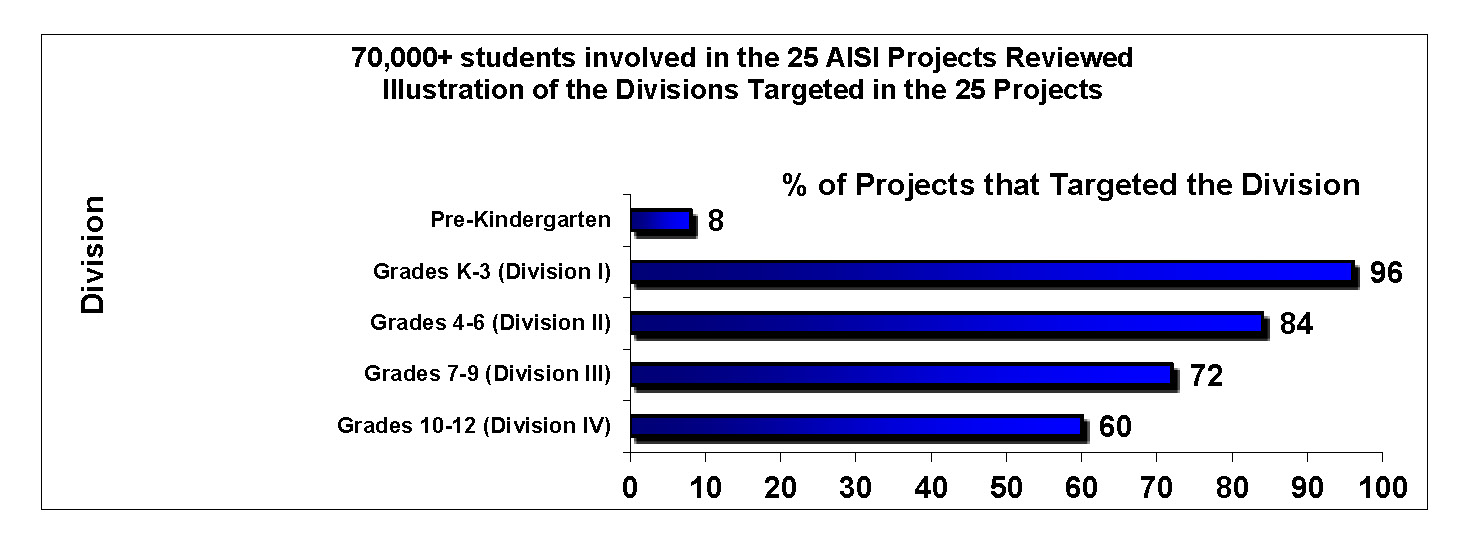

This study reviewed 25 projects carried out between 2000 and 2008, involving more than 70,000 students across kindergarten–Grade 12. These 25 projects were identified out of a pool of more than 1,600 AISI projects as having a positive effect on student learning. The research team recognized the diversity and variance of data gathering methods and measures represented by the AISI projects under review for this report, and point to this as a limitation of the study.

The site-based research data from these 25 AISI projects was drawn from diverse milieus (rural, urban, large and small school districts, and elementary and secondary schools) and points to leadership as key to sustainability. Therefore, consideration in this article is given to the potential relationship between leadership and sustainability of school improvement.

As noted in the book Celebrating School Improvement (Parsons, McRae and Taylor 2006), site-based research conducted by many of the school authorities within AISI has contributed to their own contextualized understanding of school improvement through a reflective (and iterative) process of research and inquiry. This work has led many school authorities towards innovative instructional strategies, ingenuity, educational practices and a profound knowledge of the environments within which they support student learning. Therefore, when referencing the term “innovation” in AISI projects, we point specifically to new learning or educational practices for the community undertaking the AISI project(s), and recognize that what might be innovative in one setting is not necessarily so in another school improvement setting.

Throughout this report, “AISI project” refers to one or more of these three data sources. Quotations included in this report under the sections entitled “In their own words…” have been drawn directly from the reviewed AISI project reports, focus group and telephone interviews. Quotations have been put forth in a verbatim fashion so that the voice of the AISI community is clear.

Key Findings Identified

A number of themes, strategies and challenges were identified through analysis of the reviewed project reports and further elaborated upon in the daylong focus group interview and through telephone interviews. The main findings below are not ranked in any particular order.

- Leadership: These themes pertain to formal and informal leadership roles, characteristics and practices that directly and indirectly influence educational innovation intent on improving student learning.

- Sustainability: These themes pertain to values, practices and structures that sustain educational innovation.

Although leadership and sustainability are presented here as distinct themes, they are not mutually exclusive. The conclusion of this article emphasizes the potential relationship between leadership and sustainability of school improvement, and recognizes that formal and informal leadership empowers participation, and sustains a shared vision around school improvement.

1. Leadership

1.1. Principal leadership is critical in establishing the vision for the AISI project, promoting broad participation and championing the project over the three-year cycle. Formal principal leadership was seen as critical in establishing the vision for the AISI project, and managing, supporting and championing the project long term.

In their own words…

A vital factor for success is the "buy in" of school administrators. When school administrators are actively involved and visibly supportive, significant positive changes can occur. It is a lonesome, frustrating journey for individual lead teachers, classroom teachers and project consultants, without the critical support of administration.

1.2. AISI coordinators, AISI lead teachers and AISI school leadership teams are responsible for mobilizing and coordinating school improvement initiatives over the course of the project. The coordination of the school improvement initiative was complex work. School and school district administrators often identified an individual or group of individuals to mobilize and coordinate AISI projects. AISI coordinators often served as bridging networks in the form of “middle leaders” or “boundary spanners” as they worked with teachers, administrators and central office.

In their own words…

All project members shared in the management and coordination of schedules, budgets and administrative tasks. What has been created is a culture of collaboration and interdependence. This allows all project initiatives to continue when new members come in and others drop out.

1.3. Distributed leadership among formal and informal leaders contributes to capacity building. Capacity building was enhanced through the distribution of leadership. Different school members assumed formal and informal leadership responsibilities as dictated by a given situation and based on the expertise of the individual. Establishing strong relationships and trust was believed to be central to teacher motivation, commitment and learning.

In their own words…

This AISI project provided capacity-building opportunities to teachers through a variety of activities (workshops and mentorship). It was also conceived to distribute leadership through the Literacy Lead teachers who would share new ideas with their colleagues at their schools.

1.4. Frequent communication with multiple constituents (for example, district office personnel, community, parents, students and educators) is integral to successful implementation of school improvement projects. Communication strategies were used to engage others in AISI initiatives by raising awareness, generating inspiration, mobilizing knowledge and celebrating progress. Coherence appeared to be tightly coupled with communication and knowledge mobilization.

In their own words…

Over the three years teachers have gained a professional confidence that they have started to share with parents. Teachers are sharing professional readings with parents, information from conferences they attended and new knowledge they have gained about their children. There is a new spirit of collaboration between teachers and parents in schools.

2. Sustainability

2.1. Sustainability of school improvement initiatives depends on the commitment and care of the school community. Sustainability was cultivated within the school community by developing a shared purpose focused on improving educational opportunities for all students. The commitment to student learning was at the forefront of decision making. This deep care for students in many instances has resulted in long-term integration of effective educational innovations and a change in the focus of the school community’s activities.

In their own words…

Working on this project has confirmed my belief in the importance of relationships. In my work with groups of Literacy Lead teachers or in mentoring individual teachers, the establishment of collegial 1:1 relationships based on mutual trust and respect were instrumental in the implementation of changes to teaching practices.

2.2. Sustainability is enhanced when schools and districts are professional learning communities. Individual and collective learning, inquiry and reflection were seen to be central to sustainability. Changes in school and district culture had occurred in many instances as a result of the commitment to sustaining educational innovation. Professional learning communities aided in establishing a culture of collaboration for continuous improvement.

In their own words…

It is our core belief that schools must be "learning organizations" where learning is planned, valued, and celebrated for all members of the organization. Furthermore, this learning should be focused around key themes and should provide for multiple opportunities for shared experiences in terms of large group (whole school), small group (study teams, peer observation, etc.) and individual (action-research)… Therefore, the on-going development and enhancement of professional learning communities within schools and across the district is an essential component of this project.

2.3. Integration, coherence and alignment of school improvement initiatives is a complex process of change and innovation. In the 25 AISI projects reviewed for this report, “change” was seen as a process, not an event. Fundamental shifts in professional thinking and the integration of new practices had occurred over time. There was an optimistic and expansive view of change that acknowledged the tension between innovation and sustainability.

In their own words…

Cycle 1 invited teachers to become leaders, to participate in sustained professional learning, to engage in professional dialogue around teaching and learning, to understand what student talk, process and product were telling them. Once this became a part of teacher practice there was no going back. Teachers viewed literacy differently. As a result, some of the school-based initiatives translated and expanded in the Cycle 2 project and by Cycle 3 became embedded in “what teachers do.”

Key Sustainability Strategies

The following strategies were identified from the analysis of the AISI reports, the focus group interview, and telephone interview data, as shown effective in regard to sustaining and integrating school improvement initiatives:

Mobilizing and coordinating the AISI project by

- creating structural, organizational and cultural changes;

- developing “new” leadership positions, roles and approaches;

- adapting and reallocating existing resources;

- identifying and providing “new” resources;

- aligning current AISI goals with school and school district goals, as well as with previous AISI project goals; and,

- valuing, promoting and enabling teacher collaboration, leadership, learning and inquiry.

Common Challenges

While not all projects experienced the same leadership and sustainability challenges, the following were frequently noted:

- Coordinating resources for AISI projects (for example, budgeting, project planning, scheduling, staffing and resource acquisition).

- Securing engagement and commitment from school members over time (including administrators, teachers, students, parents and others within the community) and maintaining momentum around change and innovation in educational practices.

- Staff turnover and succession planning at the school and district levels to ensure continuity and coherence.

- Managing workload and fatigue resulting from ongoing change and the many demands placed on a school system.

- Finding time to learn, collaborate and reflect on school improvement within the context of the routine school day.

- Sustainability of current school improvement initiatives in the absence of AISI funding (for example, adequate funding and availability of resources, including release time for professional learning, technology hardware and software, substitute teachers, student books and manipulatives, teacher professional resources, guest speakers and AISI coordinator position).

- Communication and development of a common understanding of school improvement language across stakeholder groups (for example, educators, parents, students and community).

- Level of leadership concern. School divisions and size, and urban and rural.

Redefining Distributed and Situational Leadership in Large-Scale School Improvement Initiatives

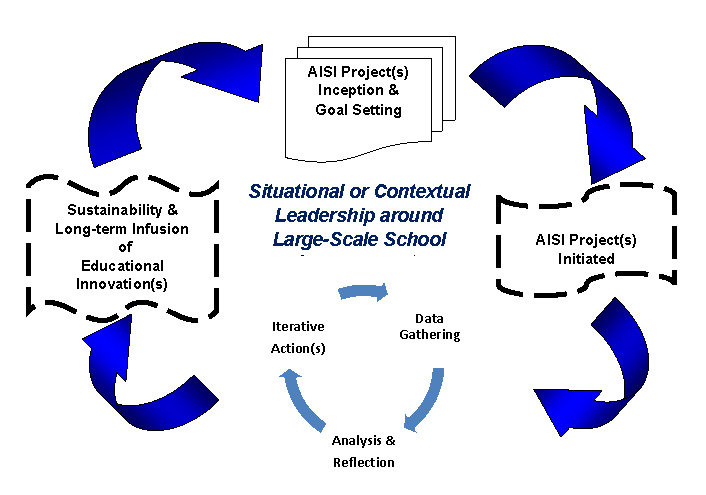

Patterns emerging from the research review of the 25 AISI projects point to AISI as a complex adaptive system and make it necessary to think about the distribution of leadership in new ways. In instances where AISI projects were deemed to be successful in terms of having a positive influence on student learning, the pattern of leadership distribution was consistent and predictable, and changed and evolved over the three-year cycle. This flow, as depicted in the diagram “Situational or Contextual Leadership around Large-Scale School” suggests that successful projects were typically overseen by a designated individual or group (for example, the AISI project coordinator, community steering committee, lead teacher(s), superintendent(s), parents, students, principal or a middle management team) from project inception until the full integration of the educational innovations into daily school life. Although other school members were also invited to participate in project leadership and tasks, the leadership of the designated AISI project coordinator(s) was critical in championing the project, motivating school members over the duration of implementation, and developing strategies to ensure the integration of promising practices. The leadership structures emerged and were sustained as needed throughout the very contextual nature of the AISI project(s) that had been shown to improve student learning.

This diagram depicts the interconnected flow of large-scale school improvement that is structured by the AISI project development, funding, implementation and reporting cycle. Throughout this cycle, the AISI coordinator(s) is highly focused on sustaining cohesiveness and commitment. At the same time, the AISI coordinator(s) assists school members as they respond to changing situations. Adaptation to change is dependent upon collective, collaborative and caring efforts orchestrated within the school community. Leadership also emerges from multiple members of the school community in the form of steering committees, student leaders, parental involvement, principal leadership, superintendent commitments or as the AISI coordinator(s) facilitates and develops leadership capacity—different school community members are provided time and space to learn and develop the skills and disposition to adopt leadership behaviours within particular situations. In addition, the AISI coordinator(s) nurtures understanding of and between school members involved in the project. Therefore, within this study, situational leadership is defined more broadly and extends beyond the leadership of the school principal or board office personnel. New forms of situational leadership, as evident in the strategic creation of the AISI coordinator(s) role along with the natural emergence of teacher leaders, were viewed as resulting in greater sustainability and coherence within school improvement initiatives.

Projects in AISI Cycle 1, and to some extent Cycle 2, appeared to be more linear in orientation and had clearer beginning and end points. By comparison, Cycle 3 projects are more cyclical in and adaptive by nature, suggesting a progression from linear to more organic change process. The stages in Cycle 3 blurred as educational innovations are infused and continuously adjusted within increasingly complex adaptive learning systems.

Focus Group—Voices of the Participants

The intent of a focus group interview was to triangulate the data derived from the analysis of the annual reports of the 25 AISI projects under review, and to provide a more nuanced understanding of the key findings. In addition, the research team wanted to probe participants’ perceptions of the needs, issues, lessons learned and challenges in each of the projects. The focus group interview also opened up a space for the project’s representative (for example, the individual(s) from the school authority with the most intimate knowledge of the project) to provide leadership and sustainability advice for others interested in longitudinal school improvement. The findings from this focus group interview include responses from 20 schools and districts drawn from the 25 selected AISI projects. Details about the research method and instruments used within the focus group interview can be found in the appendices accompanying the full report (www.education.alberta.ca/aisi).

Participants’ Advice

What advice would you give to key decision makers (teachers, principals, government leaders, faculties of education) about sustaining educational innovation and the leadership roles, responsibilities and approaches that contributed to the success of your AISI project?

In their own words…

The leaders involved must be committed to the AISI vision and all must be on the same page. A person cannot be “assigned” as the leader—he or she must believe and be committed to it.

The principal has to be a key player in the projects. Embedded professional learning is also critical.

Leadership is critical, but don’t let it reside in one person.

Effective leaders build sustainability. An effective leader will make himself/herself become obsolete. An effective AISI coordinator should almost be able to work themselves out of a job.

Nurture and keep leaders in positions long enough so that they can experience the change process through all of its challenges and highlights, so they can problem solve and adapt, and so they can provide continuity and system memory or legacy.

Sort out what to sustain and what to let go. Do less and do it better and deeper.

... develop a culture of inquiry ... each cycle poses more questions to consider and explore—what is this student work telling us? What questions does this data raise?

... listen, collaborate and be persistent about providing teachers job-embedded time to study and reflect on their practice.

Quit responding to the noise! Protect the spaces where learning happens, and reward demonstrable commitment and change, not just flashy innovation.

To promote sustainability, leadership must be shared and new leaders provided with support.

Policies and Initiatives need to be in alignment.

Dream big … imagine possibilities.

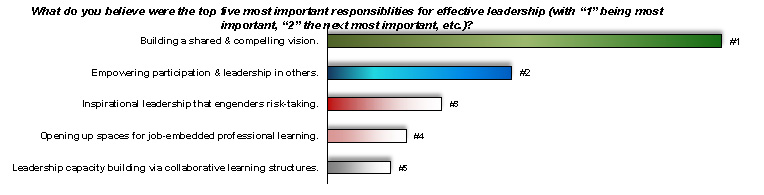

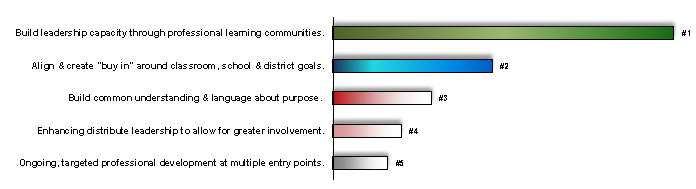

Focus Group Participants’ Perceptions of What Works

During the focus group interview the participants were presented with a list of 18 responsibilities for effective leadership in school improvement, and a list of over 20 sustainability strategies for improving schooling. These two lists were developed based on the research team’s analysis of the 25 AISI annual reports. The participants were then asked to rank order what they believed to be the top five responsibilities for effective leadership (Figure 1), and top five sustainability strategies (Figure 2) based on their experiences in leading and sustaining school improvement. [1] The following two figures illustrate the focus group participants’ perceptions:

Figure 1. Perspectives on `Top Five` Responsibilities of Effective Leadership

Figure 2. Perspectives on `Top Five` Strategies to Sustain Educational Innovations

Of note is the interdependent relationship between the top five leadership responsibilities and top five strategies for sustainability strategies. For example, the top leadership responsibility was perceived to be “building a shared vision.” Strategies for sustainability numbers two and three suggest more concrete and practical ways of how to do that (for example, “align and create ‘buy in’” and “build common understanding and language about purpose”). The number one strategy for sustainability that participants identified, “build leadership capacity through professional learning communities,” closely resembles the fifth most important aspect of leadership effectiveness that participants identified. Other similarities can be seen: between number two from the leadership list, and number four from the sustainability list; and between number four from the leadership list, and number five from the sustainability list. This finding along with others presented in this report, support the research team’s claim that there is a significant and important relationship between leadership and sustainability in the 25 successful AISI projects selected for this research review.

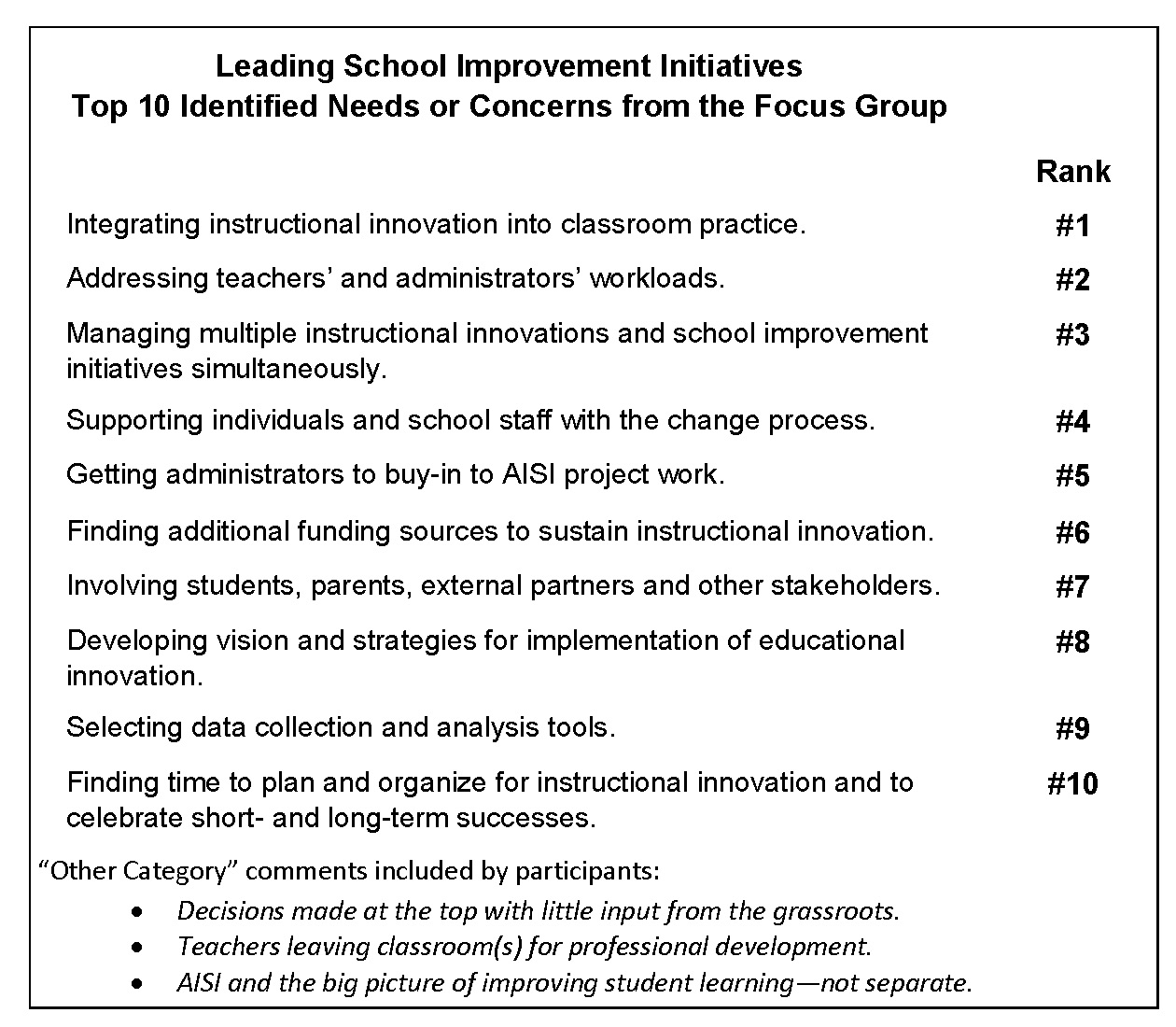

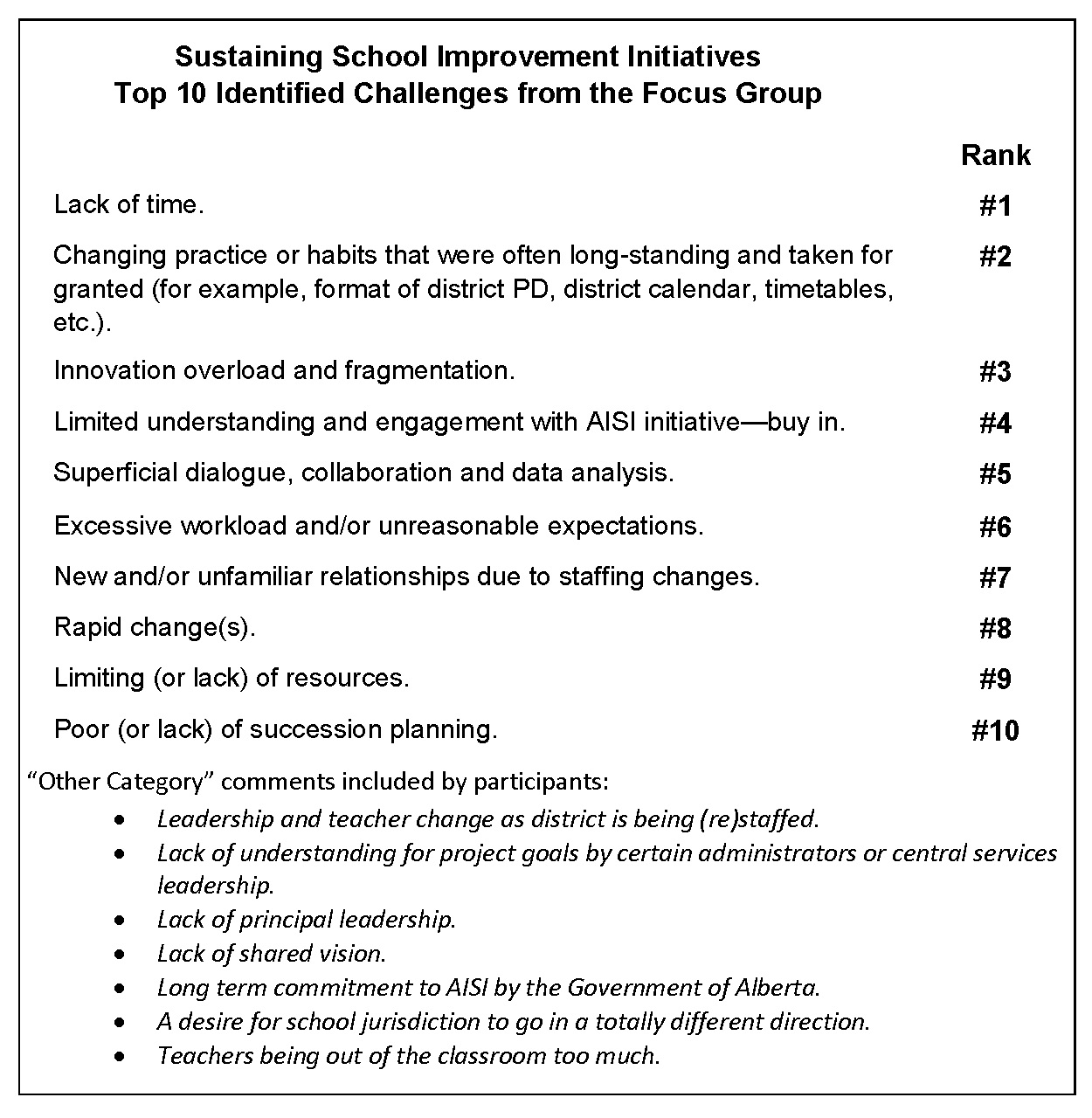

Future Challenges and Needs

During the focus group interview, participants were presented with a list of 15 needs or concerns in leading school improvement, and a list of 15 challenges to sustaining school improvement. These two lists were developed based on the research teams’ analysis of the 25 AISI annual reports. The participants were then asked to rank order what they believed to be the top 10 in each case, based on their experiences. They were also given the option to include a description of “Other” needs, concerns or challenges. The top 10 needs and concerns in leading school improvement are displayed in Figure 3, and top 10 challenges to sustainability are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Focus group participants’ perspectives on the most pressing needs or concerns related to leading school improvement initiatives.[2]

Figure 4. Focus group participants’ perspectives on the most pressing challenges related to sustaining school improvement initiatives.[3]

Conclusion

In closing, it is clear from our reconciliation of the annual project reports, focus group interview and contemporary research findings around school improvement, that AISI is (and has) positively contributed to knowledge about the complexity of and challenges of the implementation, sustainability and long-term integration of large-scale educational innovation. Although leadership and sustainability were presented throughout this report as distinct themes, they are not mutually exclusive. Specifically, this research review suggests a potential relationship between leadership and sustainability of school improvement and recognizes that formal and informal leadership empowers participation and sustains a shared vision around school improvement.

Despite the diversity and variance of data gathering methods and measures represented by the 25 AISI projects under review for this report, there was a high degree of consistency of themes and issues. The research team believes it is significant that findings from the analysis of the written AISI project annual reports, and from the data collected during the focus group and telephone interviews, are also confirmed to a large extent by the research literature. Such consistency is encouraging, not only in that it suggests a high degree of credibility and integrity of these findings, but also because it suggests there are leadership approaches that can, with sustained school improvement strategies and a growing wisdom, shape schools into positive teaching and learning environments for all.

However, the research team acknowledges that the site-based research conducted by the 25 school authorities in the projects reviewed has also contributed to each authority’s own contextualized understanding of school improvement. Through a reflective process of inquiry and research, each particular community of learners developed innovative instructional strategies, educational practices, and a profound knowledge of the environments within which they support student learning. The pragmatic ways by which the AISI projects reviewed could address issues and solve problems unique to their needs and circumstances has been captured by the research team, with the intent of supporting larger system-level knowledge mobilization.

Review of the selected AISI projects and data collected from focus groups and telephone interviews revealed a number of questions, ambiguities and tensions identified by the participants. Also, as the research team compiled this review, other questions emerged from data analysis and synthesis. Therefore, as this study draws to a close, the research team suggests that further studies need to be undertaken to explore the following:

- The extent that middle and high schools use distributed and situational forms of leadership.

- Strategies to measure cultural shift that occur within one or more AISI cycles.

- How situational or contextual leadership is defined and enacted within AISI and other school contexts.

- The alignment and interdependencies that exist between schools and stakeholders, and policies and practices related to large-scale school improvement.

- The extent to which knowledge mobilization, leveraged through AISI, is sustained over longer periods of time. That is, what kind of leadership is required to sustain the educational innovation and integrate it into day-to-day practice? How are AISI practices integrated so they become both a conscious/unconscious way of being?

- The role of the superintendent. Given the relative absence of attention given to this formal position within the AISI Projects Annual Reports and focus group conversations, additional research needs to explore how the superintendent and other senior system-level administrators are implicated in leading and sustaining educational innovation.

- Complexities of the role of the AISI coordinator that are brought into middle leadership positions. Moving from the broad district level, into the classroom, and at the school. The tensions in the divide between the different leadership positions and expectations, scope or size of the jurisdiction and the implications of moving in and out of the different positions, and the tensions that this causes.

Project findings, provincial reviews and accompanying site-based research needs to be shared among stakeholders and should inform ministry and jurisdictional policy, processes, programs and practices. It is the hope of the research team that those reading this review of the research will pause to summarize and celebrate AISI’s successes, take time to reflect on what we have collectively learned through AISI, and consider how AISI can help us face future educational challenges within individual school authorities and throughout the province. Based on what the research team members found through this study, they believe that out of future cycles of AISI will evolve profound understanding of the relationship between leadership and sustainability of educational innovation, as school authorities continue to redefine the notion of distributed and situational leadership in the context of large-scale school improvement initiatives.

References and Recommended Resources

Alberta Education. 2008. Knowledge Dissemination and Integration Plan 2008. Edmonton, Alta.: Alberta Education. Alberta Initiative for School Improvement (AISI) website. http://education.alberta.ca/admin/aisi.aspx (accessed July 12, 2008).

Burger, J., C. Webber and P. Klinck, eds. 2007. Intelligent Leadership. Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

Dufour, R., and R. Eaker.1998. Professional Learning Communities at Work: Best Practices for Enhancing Student Achievement. Bloomington, Ind.: National Educational Service.

Foster, R.Y. 2005. “Leadership and Secondary School Improvement: Case Studies of Tensions and Possibilities.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 8, no.1: 22–34.

Fullan, M. 2005. Leadership and Sustainability. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Corwin Press.

------. 2007. The New Meaning of Educational Change (4th ed.). New York, N.Y.: Teachers College Press.

------. 2003. The Moral Imperative of School Leadership. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Corwin Press.

Hargreaves, A., and D. Fink. 2006. Sustainable Leadership. San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass.

Hersey, P., and K. Blanchard. 1996. “Great Ideas Revisited: Revisiting the Life-Cycle Theory of Leadership.” Training & Development 50, no. 1: 42–47.

Hopkins, D. 2005. The Practice and Theory of School Improvement. Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

------. 1998. “Tensions in and Prospects for School Improvement.” In International Handbook of Education Change, eds. A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan and D. Hopkins, 1035–1055. Dordrecht, NL: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Lambert, L. 2002. “A Framework for Shared Leadership.” Educational Leadership 59, no. 8: 37–40.

------. 1998. Building Leadership Capacity in Schools. Alexandria, Va.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Leithwood, K., and D. Duke. 1999. “A Century’s Quest to Understand School Leadership.” In Handbook of Research on Educational Administration, 2nd ed., eds. J. Murphy and K. Seashore Louis. San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass.

Lieberman, A., and L. Miller. 2004. Teacher Leadership. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Jossey-Bass.

Osterman, K.F., and R.B. Kottkamp. 2004. Reflective Practice for Educators: Professional Development to Improve Student Learning, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Corwin.

Parsons, J., P. McRae and L. Taylor. 2006. Celebrating School Improvement: Six Lessons Learned from Alberta’s AISI projects (2nd ed.). Edmonton, Alta.: School Improvement Press.

Shields, C., and M. Edwards. 2005. Dialogue Is Not Just Talk: A New Ground for Educational Leadership. New York, N.Y.: Peter Lang.

Spillane, J. 2006. Distributed Leadership. San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey Bass.

Spillane, J., and J.B. Diamond. 2007. Distributed Leadership in Practice. New York, N.Y.: Teachers College Press.

Taylor, L., L. Servage, P. McRae and J. Parsons. 2006. Alberta Initiative for School Improvement (AISI) Collaborative Professional Development Research Review: Relationships, Leadership and Ownership. Edmonton, Alta.: Alberta Education. www.education.gov.ab.ca/k_12/special/aisi/pdfs/AISI_Colla_PD_Research_Review.pdf (accessed July 20, 2008).

Wright, L. 2008. “Merits and Limitations of Distributed Leadership: Experiences and Understandings of School Principals.” Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy 69: 1–33.

Yukl, G. 2002. Leadership in Organizations, 5th ed. Upper Saddle, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

________________________

Dr. Rosemary Foster is a professor in Educational Administration and Leadership at the University of Alberta. She works with undergraduate students aspiring to be teachers and with graduate students in educational administration and leadership. Foster was for more than 20 years a high school teacher and administrator in the public school system in Alberta.

Dr. Lisa Wright is the principal of Avonmore School, in Edmonton. She holds a PhD in Educational Administration and Leadership from the University of Alberta. Wright is conducting research in principal identity within the context of school improvement and the reflective and reflexive practices of school leaders.

Dr. Phil McRae is an executive staff officer with the Alberta Teachers’ Association and an adjunct professor with the Faculty of Education, University of Alberta, where he earned his PhD. He was the director of the Alberta Initiative for School Improvement at the U of A from 2005–09. McRae has taught in many educational settings while living in the United Arab Emirates, Japan, Spain and Lethbridge Public School District and on the Blood (Kainai) Reservation in Alberta.

[1] The ranking reflects the number of respondents and an average of weights assigned to the selected responses, with 1 being the most important responsibility or most effective sustainability strategy identified. N=19.

[2]The rank reflects the number of respondents and an average of rank weights assigned to the selected response, with 1 being the most pressing need/concern or challenge identified. N=19.

[3] The rank reflects the number of respondents and an average of rank weights assigned to the selected response, with 1 being the most pressing need/concern or challenge identified. N=19.