Page Content

Inclusion—Alberta’s educational palimpsest

In ancient times (long before Twitter and ages before paper), people used to write on parchments made of animal hides. Because such hides were in short supply, the writers would often efface the original writing when they wanted to add new material. These hides, with their layers of texts from different times, are known as palimpsests.

One famous example, found in the British Museum, is a double palimpsest in which a text of St. John Chrysostom, in Syriac, of the 9th or 10th century, covers a Latin grammatical treatise in a cursive hand of the 6th century, which in turn covers the Latin annals of the historian Granius Licinianus, of the 5th century. Another is the Novgorod Codex, where potentially hundreds of texts have left their traces on the wooden back wall of a wax tablet.

The Alberta government’s policy on inclusion in schools has become reminiscent of ancient palimpsests by continually reoccupying the same space with an unending series of revisions, scribbling and new texts. It’s not that the intent is malicious—it’s just doing the same thing over and over.

Though the Progressive Conservative party attained office 40 years ago, progress on matters related to inclusion and equity has been painfully slow, and the government continues to sidestep claims that there are a lot of people in this province who cannot be said to be enjoying the “Alberta advantage.”

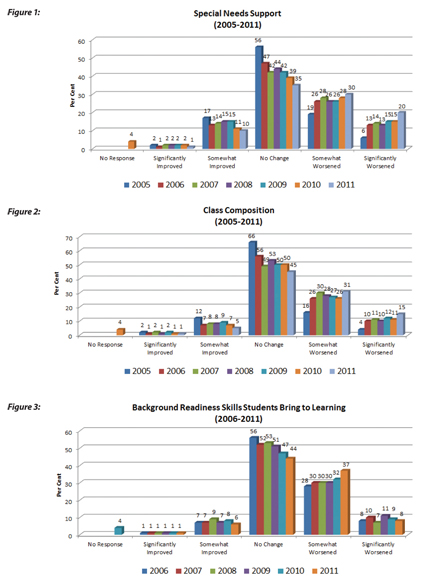

A few findings from Association research, including the annual Member Opinion Survey, illustrate the government’s long-standing unwillingness to respond to the needs of the most disadvantaged in this province. Data since 2005 shows that in the eyes of Alberta teachers, support for students with special needs has declined dramatically. As the chart below illustrates, in 2005, 25 per cent of teachers reported worsened support for students with special needs. This number rose to 39 per cent by 2008 and to 41 per cent in 2009, and hit 50 per cent this past year. Initial improvements in support for students with special needs (immediately after the 2003 Commission on Learning) appear to have slipped after 2005. Over the past six years, analysis of the data by region suggests that the erosion in supports for students with special needs has been consistent across the province.

When asked about class composition and supports for dealing with the growing diversity and complexity of classrooms over the past six years, teachers report worsened conditions. In 2005, 20 per cent of teachers indicated declining support; this figure rose to 46 per cent in 2011. Given Alberta’s dramatic population growth (there will be 4.6 million of us by 2035), this data illustrates that we are not investing in a future asset—our diverse and vibrant population.

Inclusion: Start it right in the early years

A good start in achieving inclusion in Alberta schools would be to go beyond the government studies and pronouncements on inclusion and concentrate on what it means to be a community. A society’s commitment to supporting living and learning in the early years of life is the foundation of inclusion.

In the view of Alberta teachers, student readiness to learn continues to be a long-standing area of concern. Despite years of policy reviews and talk about such things as wraparound services, learning coaches and inclusion, the roller-coaster funding, including a freeze on increases in special education funding, has taken its toll. For example, as the data indicates, in 2006, 36 per cent of teachers reported a decline in student readiness to learn; this number rose to 45 per cent in 2011.

For Albertans, the fallout from years of government’s continual rewriting of policies and subsequent inaction occurred this past November with the release of the independent national Early Years Study, authored by Margaret McCain, Dr. Fraser Mustard, who died a week before the report was released, and Kerry McCuaig. Their research provides the social, economic and scientific rationale for investing in young children and recommends that all children be entitled to an early education from age two. The study says that early education improves school readiness, graduation levels, future earnings and health.

The independent report ranked each province on its early education services according to 15 benchmarks that reflect a common set of core standards essential for the delivery of quality programming. Benchmarks were organized into five categories: governance, funding, access, learning environment and accountability. Each category is given 3 points, for a total of 15. Standings by province in the Early Childhood Education Index out of 15 points are indicated in the following list. Resource-rich Alberta is second last out of 10 provinces.

Early Childhood Education Index (out of 15) Standings by Province

- Québec: 10 (67 per cent)

- Prince Edward Island: 9.5 (63 per cent)

- Manitoba: 7.5 (50 per cent)

- Ontario: 6.5 (43 per cent)

- Nova Scotia: 5 (33 per cent)

- British Columbia: 4.5 (30 per cent)

- Saskatchewan: 4.5 (30 per cent)

- New Brunswick: 4.5 (30 per cent)

- Alberta: 3 (20 per cent)

- Newfoundland: 1.5 (10 per cent)

Alberta cannot afford to ignore the structural obstacles to student readiness to learn. Guaranteed universal access to early childhood education and a comprehensive community-based approach to enhancing the well-being of children and youth are essential to achieving the vision of the government’s Inspiring Action agenda. Current piecemeal government policies on readiness to learn continue to fall short. As noted in a recent report by Public Interest Alberta, Head Start executive director Kathy Lenihan points out that the provincial preschool program for low-income families turns away 900 needy families each year. She said children from impoverished families suffer high levels of dental problems, learning delays and interpersonal troubles, partly because parents lack adequate supports.

Complacency is also our worst enemy: one out of 12 Alberta children lives in poverty, yet so many Albertans are materially among the richest people on the planet. Courage and decisive action are required to counter the effects of public policies that exclude, marginalize and ignore the systemic day-to-day problems faced by Alberta’s children and youth.

Inclusion is a text that is rewritten every day in Alberta classrooms. For example, Alberta teachers continue to contribute $900 per year out of their own pockets to buy school materials and classroom resources. In fact, 60 per cent of teachers reported in 2010 that they could not carry out their teaching assignment without buying materials with their own money. Gender plays a role, too, in the continual rewriting of the inclusion story in Alberta. As our annual Member Survey and Five Year Beginning Teacher study have shown, younger, female teachers are the most likely to provide their students with subsidized materials and supports out of their own pockets. And teachers with early childhood services and elementary assignments and classroom-only responsibilities are the most likely to subsidize their school’s budget with their own financial resources.

Inclusion: Valuing equity in community

In terms of public policy, equity is best defined as providing the least advantaged with the most resources.

—Ben Levin, professor, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education

Ben Levin, one of Canada’s most respected educational policy analysts, made the above statement about equity in a presentation last fall to Alberta school district leaders, where he also urged the audience to stop arguing about policy on inclusion and “focus on doing what we already know needs to be done”—helping those in need.

Levin’s provocation was timely. With the potential for the education sector to be distracted by yet more changes in policy and political direction (we have the potential for yet another minister of education and a provincial election will be held this spring), it is time for action. No longer can we afford to treat inclusion as Alberta’s educational palimpsest; we can no longer afford endless policy chatter and consultations that distract us from definitive action. As the Association’s The Courage to Choose study outlined in 2010, the choices identified by an international panel of experts cannot be about tweaking current government policies on excessive managerialism, burdensome bureaucracy and technology boosterism. High-performing education systems will focus on two areas: (1) building a culture of responsibility and trust that values teacher professionalism in judging what is best for students and (2) providing sustained resources to create great schools for all students.

For too long inclusion has been overmanaged and underimagined. As noted in The Courage to Choose, inclusion, as with much of the K–12 sector, is not a policy or brand name but a set of deliberate innovations and actions driven by a commitment to the core value of equity through the following:

•creating flexible frameworks that encourage locally determined, educationally sound policies that recognize how diverse and complex schools are;

•fostering ethical pedagogy on teaching and learning for deep and enduring understanding both within and for community;

•building a culture of trust among education partners; and

•bringing forward the best from the past while constantly encouraging innovation.

_________________

Dr. J-C Couture is the ATA’s associate coordinator of research.

Sources for the statistics and references cited in this column are available upon request by contacting J-C Couture. E-mail: jc.couture@ata.ab.ca.