Page Content

Learning teams assist students with special needs

Imagine being transported to a foreign country where no one spoke your language; where such norms as establishing eye contact with strangers and ideas of personal space were very different from what you knew. Imagine how you’d feel as you navigated your way through a vastly different world where none of the normal rules applied. You’d be tired, anxious and overwhelmed as you tried to make sense of new social expectations.

Next, take a moment to think about all the things that make you socially able in your day-to-day life. Different factors enter into play when you process a social situation. You can perceive social situations accurately, decide what skills to use and use those skills on the fly, tweak what you do based on social feedback and the situation, and when you need to, emulate the behaviour of others in order to be more successful. For many of us, being socially able takes little effort.

However, not everyone processes information in the same way. People with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can sometimes feel like as though they have been transported to a foreign country where none of the norms apply. This is because people with ASD process social information with their intellect rather than with their gut (Attwood 2006) and, as a result, many students with ASD find social interaction overwhelming—they often find it difficult to initiate, participate in large groups, connect emotions to social situations, consider the perspective of others and maintain conversations with others (Bauminger, Shulman and Agam 2003).

Assisting students with ASD

Social skills are foundational for all students and are a cornerstone of programming for students with ASD. When we are establishing goals related to social skills for students, three questions must be asked: What is doable? What is functional? How will programming be accessed?

Educators want students to succeed, and to develop social and communication skills. However, goals that are too difficult can cause students more anxiety. Therefore, ask yourself, What resources do I have in my classroom and school community? Do I have space for different kinds of instruction? Is there a quiet space that students can access to help them with emotional regulation? What does the student’s daily routine look like? Are there opportunities for successful social interaction in a meaningful setting? What strengths do students have that I can capitalize on to help move progress?

When looking at what is functional, answer the question: Why is this skill important for the student? As you determine appropriate social skills and goals for a student with ASD, think about what will have the biggest effect on the student’s quality of life. Consider what your goal is and work backward from it, recognizing that there may be many steps between a student’s current level and where you’d like him or her to be.

To make a student’s goal accessible, start with the least intrusive intervention and work backward. Engineer the environment for all students so that everyone knows what the social expectations are before an activity begins (for example, classroom, assemblies and festive activities—Christmas, Easter, Halloween). Explain expectations by referring to classroom rules, visual schedules, modelling and instruction. To maximize accessibility, ensure that the goal is socially appropriate for the student (for example, Duck, Duck, Goose is probably not the best social game for 16-year-olds) and that it is implemented to minimize the student’s alienation from peers. Remember, the goal is to give students the feeling of success every day and to develop their social skills and self-confidence.

Once you have established goals, the school’s learning team (teaching partners, administrator and consultant) will want to consider whether it is a lack of skill or motivation that is affecting the student’s ability to interact successfully. A lack of skill means that the student cannot determine the correct response in a social situation. In this case, the learning team will look at direct instruction of skills. If the student shows a lack of motivation this means that the student can determine the correct social response out of context but does not demonstrate the skill when it is needed. The learning team needs to look at the function of existing behaviour and the level of reinforcement.

People with ASD can have difficulty accurately processing the big picture. For example, they may focus on inappropriate stimuli in the background or the words a person says, while disregarding the tone or failing to notice body language that might indicate that the student’s communication partner is uninterested. Many strategies we use with ASD students involve helping them attend to the appropriate stimuli, offering better ways to interact with others and providing structure and routine to social situations that can be completely unpredictable.

Joint Attention

One of the first skills a learning team may consider developing in students with ASD is joint attention, which refers to a person’s ability to share an activity or experience with another. We watch the activities a student gravitates toward and look for opportunities throughout the day to play with the student. We watch the way the student plays and imitate the appropriate actions he or she engages in. The educator should be at the student’s physical and expressive language levels—when developing joint attention it’s important not to overwhelm the student with too much language or too high expectations.

Play should occur in relevant, naturally occurring and age-appropriate situations. Make sure that you choose an activity you know the student will enjoy, based on observation, but one that is not so motivating that the student will not focus on anything else. Build in opportunities for taking turns; that is, imitate the student’s behaviour and wait to see if the student repeats the same action. If the student does, reinforce him or her for doing so and let play continue. Make sure your turns are balanced and that it stays at a level that will keep the student engaged. This means that you may sneak in one turn for every four of theirs.

When working on joint attention, it is important to pick times of day that work for the student and the learning team. This means avoiding times when the student is overwhelmed or stressed, such as the major transition near the end of the school day when the student is focused on heading home instead of the play activity.

As the student starts to attend more to others, it may be a good time to teach the student about emotions and body language. Start by having the student identify the emotions in pictures of family, classmates and school staff. Start with the base emotions, such as happiness, sadness, anger and fright. You can use pictures to teach body language, and as the student becomes more fluent in identifying emotions, introduce pictures in magazines or short clips from YouTube (with the sound turned down). You can also people-watch with the student, observing people from a distance and trying to figure out how they are feeling.

Peers are an excellent resource to tap into when developing a student’s social skills. Peers can teach, reinforce and simplify social skills, and can sometimes be a more effective model than teachers, particularly if those peers can be reinforced using the same rewards the student with ASD finds motivating. A good peer is someone a little bit older than the student; he or she should be flexible, cooperative, kind, assertive, and able to follow directions and stay on task, and should possess the skills that teachers want students to learn.

Play Scenarios

Some students with ASD are good at exploratory or constructive play (for example, playing in the sand or building with Lego) but have difficulty with pretend play or playing games with rules. For students struggling with pretend play, teachers might use structured play scenarios to teach the student new skills. By creating imaginative scenarios with toys, actions and words, teachers provide a foundation that the student uses to interact with peers. Scenarios to consider are holding a tea party, building with blocks, going to a restaurant, visiting the doctor, going to a birthday party and riding the bus. Regarding the last item, you could arrange chairs in a line, with a larger chair at the front as the bus driver’s chair. Students board the bus; the student in the driver seat talks to the riders, using scripts such as “Everyone sit down” and “Let’s go for a ride”; the driver pretends to drive to the bus stop. When the bus arrives, everyone gets off and a new bus driver has a turn.

Another way to teach play scenarios is through video modelling. Video modelling helps students with ASD focus on the right stimuli by zooming in the camera on important details. Editing, voice-overs and appropriate subtle background music help engage the student during the video. Play the video daily and have the student work on each step of the play scenario as he or she watches that step on the video. By watching the video, the student gets the same instruction each time and the scenario does not change when different people interact with the student. Putting together a play scenario using video modelling requires planning, scripting and time, so make sure the entire learning team is on board before putting together a video.

The Circle of Friends

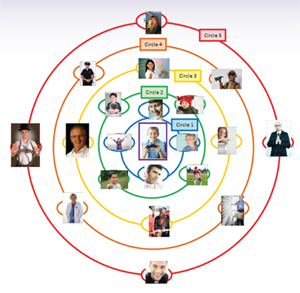

The circle of friends is a visual strategy to teach ASD students boundaries and appropriate ways to interact with those around them. The student is at the centre; each ring around the student represents a different social circle. The closer the ring is to the student, the more intimate the student can be with the people in that ring. The order of the rings around the student is (1) family, (2) friends, (3) school team, (4) safe strangers (police officers, firefighters and security guards) and (5) unsafe strangers.

The rings can be colour-coded to help the student organize the information. The learning team does not have to present all the different layers to the student at once. Instead, the team can focus on the rings closest to the student and build on the concept as understanding increases. A ring’s proximity to the student determines the kind and level of physical contact the student can have with others, the topics that can be discussed, and who is trustworthy and whom the student should avoid.

Expected and Unexpected Behaviour

Most of us recognize that our behaviour tells other people a story. When we ride an elevator by ourselves, we know that it’s OK to check our teeth and hair in the mirror as long as we’re alone. When someone else enters the elevator, we change our behaviour to keep people thinking the way we want them to think about us. Some people with autism, however, have difficulty understanding this concept. When working with older students, teachers can talk about the difference between expected and unexpected behaviours. Helping students distinguish between these types of behaviours helps them realize that there are consequences for the social behaviours they display in the classroom. This strategy needs to be implemented by someone who has a good relationship with the student, as it requires the use of frank but kind language.

Conversation Books

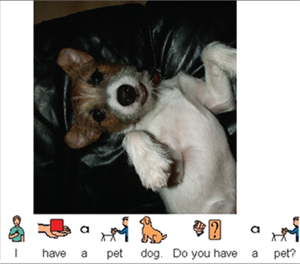

Another strategy for students who have trouble initiating and maintaining conversations is a conversation book. A conversation book provides structure and predictability to something that is rarely structured or predictable. The conversation book can feature various topics to help expand the student’s conversation repertoire (for example, family, pets, favourite activities and movies). Start by practising with someone the student is comfortable with, a peer if possible, and use the story to structure the conversation so the student can be more successful. Add and change pages as the student becomes more fluent with different topics. As the student becomes more comfortable, the conversation book can be phased out.

Helpful Tips

Remember to talk in a quiet place. Students with ASD process social information much more consciously than other people. The more distractions there are, the more difficult it is for them to focus. Don’t be offended by direct honesty when working with students with ASD. Some people with autism do not know how to respond to compliments and praise. Avoid sarcasm when working with an ASD student because the student might focus on the words you use rather than on your tone.

Whatever your team decides, make sure it is the least intrusive plan possible. This way, promoting generalization will be easier to do. Include everyone on your team in your planning to ensure consistency and agreement. Collect and review data on how things are going. Look for observable and measurable things to target. Last, if you feel stuck, talk with your team—you are not alone!

Bibliography

Attwood, T. 2006. The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome. Philadelphia, Penn.: Jessica Kingsley.

Bauminger, N., C. Shulman and G. Agam. 2003. “Peer Interaction and loneliness in High-Functioning Children with Autism.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 33, no. 5: 489–508.

Champagne, M., and L. Walker-Hirsh. 1993. CIRCLES: Intimacy and Relationships. Santa Barbara, Calif.: James Stanfield.

Hart, K. I., M. Fujiki, B. Brinton and C. H. Hart. 2004. “The Relationship Between Social Behavior and Severity of Language Impairment.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 47, no. 3: 647–663.

Semrud-Clikeman, M. 2003. “Executive Function and Social Communication Disorders.” Perspectives 29, no. 2: 20–22.

Winner, M. G. 2007. Sticker Strategies—Practical Strategies to Encourage Social Thinking and Organization. San Jose, Calif.: Think Social.

__________________

Jenn Brown is a junior high science teacher with Elk Island Public Schools. She has worked with many students with special needs at a variety of grade levels and strives to build positive relationships with students, parents and other teachers.

Shane Hewitt has worked with people affected by ASD for more than 12 years. He works for Elk Island Public Schools as a consultant in Student Support Services.

Bev Thompson has worked with students with special needs from ECS onward in inclusive school programs and outreach centres.